NOVEMBER 19, 2023

KLUXEN – BACH, PROKOFIEV AND MOZART

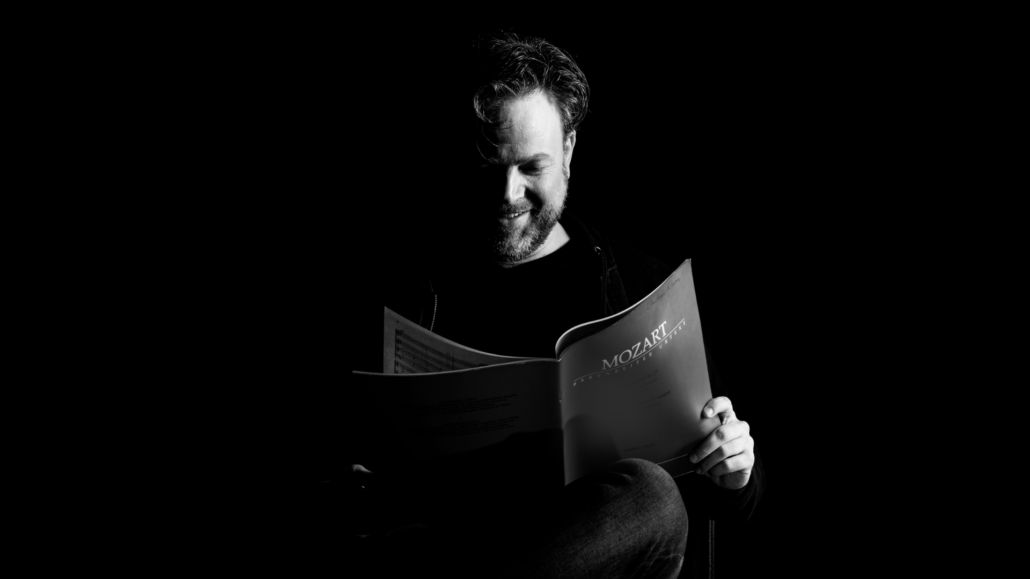

Casual listeners can be forgiven for not immediately grasping the links between Johann Sebastian Bach’s Ricercar à 6, Sergei Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto No. 2 in G minor, and Wolfgang Mozart’s Symphony No. 25 in G minor. For that, it would help to have a little otaku in one’s nature, as may well be the case with Victoria Symphony music director Christian Kluxen.

“If you are a nerd,” the conductor says, grinning, “you will see that there’s a kind of G minor theme between the two halves, right?”

There’s also at least a superficial similarity between the Ricercar’s opening motif and the Violin Concerto’s introduction, as Kluxen demonstrates by singing them in a serviceable baritone. “And I’ve always thought that Mozart and Prokofiev fit very well together in the imagination,” he continues, contending that they share a “sweet, miniature humour which is discreet and delicately served.”

Bach and Mozart—one high-minded and devout, the other heretical and prank-prone—are less likely bedfellows, but Kluxen believes that in this engaging program he’s found a way to have them coexist in happy proximity. “For some reason Prokofiev makes Bach and Mozart come together in a way, and I just think it’s wonderful,” he says. “It’s really one of my favourite programs. Simple, classy, new, not seen before: I really like it.”

For all that the Russian member of this triumvirate has been given the role of go-between, there’s little that’s diplomatic or demure about his contribution to the program. “The Prokofiev concerto is really a monster in the repertoire,” Kluxen says, and soloist Terence Tam does not argue the point.

“It is a very physical concerto, especially the last movement,” the Victoria Symphony’s concertmaster agrees. “It’s just this nonstop piece that kind of tumbles into the ending. The third movement, particularly, I think of as this kind of fiendish dance, almost a Russian beer-hall kind of theme, even though there are castanets in there too. People talk about it having kind of a Spanish theme, and I think it was premiered in Madrid. So perhaps that’s why there’s a little bit of a Spanish influence there, although to me that’s the only thing that sounds Spanish about it at all.”

Tam might be overlooking the fact that Prokofiev’s wife, the singer Carolina Codina, was Spanish. But he’s correct about the premiere: Robert Soetens, a frequent Prokofiev collaborator, was the soloist when the Violin Concerto No. 2 made its debut, in 1935, in the Spanish capital. It was a pivotal time for the composer, and the concerto’s success may have fed into the optimism he felt about returning to Russia, then under Joseph Stalin’s control, in 1936. “I care nothing for politics—I’m a composer first and last,” he wrote at the time. “Any government that lets me write my music in peace, publishes everything I composed before the ink is dry, and performs every note that comes from my pen is all right with me. In Europe, we all have to fish for performances, cajole conductors and theatre directors; in Russia they come to me. I can hardly keep up with the demand.”

As we all know, Prokofiev badly misjudged the situation in his native land, and was lucky to escape the Soviet purges of the 1930s and ’40s. It’s possible, though, that his nostalgia for the country that he left in 1918 might have coloured the Violin Concerto No. 2, which he began in Paris and finished in Baku. “The first and second movements are incredibly lyrical, and very Romantic as well,” Tam observes, although he shies away from any definitive conclusion. “It’s either a yearning to be back in Russia, or a yearning for the time that he wasn’t in Russia,” the violinist says. “Maybe it’s that he’s finding his roots with the Russian people again, or something like that. I’m not really sure.”

Also unclear is whether Prokofiev was already paying heed to Stalin’s dictum that Soviet music should be “heroic, bright, and beautiful”. The dictator certainly disapproved of non-representational art, and the Violin Concerto No. 2 is generally considered the first step in Prokofiev’s move away from his more formalist concerns. Just as the Viennese echt-modernist Anton Webern was looking back when he interpreted Bach’s Ricercar à 6 for the 20th century, the Russian composer was reappraising his own artistic lineage in this transitional work. “With the second movement,” Tam says, “if you just listen to the theme itself, you would never imagine it’s Prokofiev, right? You’d think ‘Oh, this is some other great Russian Romantic composer. It could be… who knows? It could be Tchaikovsky.

“I first heard it when I was a teenager,” the violinist continues, “and I was like ‘Oh my god, this is amazing, because it’s a side of Prokofiev that we don’t really see.’”

With its tumbling intensity, however, that final movement couldn’t have been written by anyone other than Prokofiev. Similarly Webern, even channelling Bach, could never be anyone other than Webern, and Mozart was always his irrepressible self. Truly great composers might bow to the dictates of their time, but their music transcends its moment.

Notes by Alex Varty

Christian Kluxen, conductor

Christian Kluxen, conductor Terence Tam, violin

Terence Tam, violin