Does music need meaning?

Let’s take theoretical listener A, who enjoys Japanese gagaku but does not speak a word of Japanese, doesn’t have a particularly deep understanding of the court rituals that gagaku is meant to accompany, and can barely tell a shamisen from a sanxian. The pleasure, for A, might lie in surprise, or in hearing a form of organized sound that lies out of their everyday experience, or in being ushered into an acoustic space that allows for a contemplative but not necessarily verbal experience.

Theoretical listener B, on the other hand, never fails to turn out for the local choir’s Singalong Messiah, knows the words by heart, and can place the genesis of George Frideric Handel’s masterpiece within the framework of Christian theology, as well as within the history of European art music.

The quality of A’s experience is going to be very different from B’s, but is one or the other better? For that matter, does listener C get more psychic nutrition from hearing an Iannis Xenakis string quartet than listener D does from the latest Taylor Swift chart-topper?

Frankly, we haven’t a clue, and don’t dare offer an opinion. But we do know that Pyotyr Ilyich Tchaikvsky’s Symphony No. 6 in B minor is universally hailed as one of the most moving works in the Romantic repertoire, and that it was written with concrete programmatic intent. What that program was, however, remains a mystery, even 122 years after the work’s premiere in Saint Petersburg.

Describing the nascent Symphony No. 6 to his cousin, Tchaikovsky wrote “On my journey, the idea of a new symphony came to me, this time one with a programme, but a programme that will be a riddle to everyone. Let them try and solve it….The programme of this symphony is completely saturated with myself and quite often during my journey I cried profusely.” Beyond that, however, the composer apparently never went into detail about the work’s emotional underpinnings, a situation complicated by an early translation error. In English, we know Tchaikovsky’s Sixth as the “Pathétique” Symphony, but this is only a French approximation of the Russian word pateticheskaya, used by Tchaikovsky to mean “passionate” or “emotional”. Any implication that the Sixth is purely lachrymose is clearly unfair.

It’s less problematic to consider the Symphony No. 6 autobiographical, with many suggesting that it deals with Tchakovsky’s closeted homosexuality, a love affair that failed due to the social constraints of the era, or the composer’s suicidal ideation. Others have proposed that the work is a requiem for the writer Aleksey Apukhtin—a concept Tchaikvosky shrugged off—or a more generalized meditation on fate. We’ll never know.

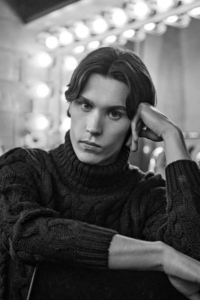

It’s likely that even more verbiage has been expended trying to “explain” Ludwig van Beethoven, who was never shy of using programmatic elements in his music. But when it comes to the Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major, soloist Jaeden Izik-Dzurko needs no narrative map to chart a gripping performance.

“I know of many people who find that to be a useful thing to do when interpreting music, but I’ve never felt compelled to do that myself,” says the 26-year-old virtuoso, who most recently won the 2024 Leeds international Piano Competition. “I’m reminded of a passage I read about Alexander Scriabin and the fact that he never wrote art songs. One of the reasons he gave was that to attach any sort of content to the pitch material was, itself, almost taking it out of this magical other realm in which it exists—almost cheapening it, in some way. That’s a very strong perspective, but I do think one of the qualities that I love about music is that it requires no reference to the physical world of appearances. It’s just purely abstract, and it sort of communicates in a more direct manner than mere speech.”

It would be folly, he adds, to resort to the written word to “approximate the feelings that the music itself offers”.

“But I would be interested to know if anyone has collected various composers’ thoughts on that question,” he continues. “To what degree does a storyline or a narrative contribute to or take away from their creative process? Certainly with some composers it seems obvious that it sparks remarkable creativity, while others have a preference for just absolute music.”

For the Salmon Arm native, now studying in Spain, Beethoven’s fourth piano concerto is primarily “a personal exploration” of music itself. “In the Piano Concerto No. 5,” Izik-Dzurko explains, “he is clearly going for a kind of gigantic, monumental, kind of sprawling effect. The rate of harmonic motion is slow in the “Emperor”, and even quite simple—one could say ‘austere’, in some ways. In contrast, the fourth concerto is extremely intricate. There’ s obviously a lot of finger work, from the pianist’s perspective, and even that passagework is itself very contrapuntally and sometimes motivically rich. Even though it goes by so fast, it’s beautifully crafted, and there’s melody in every single note.

“That was a comment I received ad nauseam from one of my teachers while practicing it: ‘This is not just finger work. Don’t let any of it go by; every single note has a particular significance, a sort of expressive inflection to it.’ That kind of writing, especially in the major mode, is rare among the piano sonatas. And then of course there’s that rather striking opening, that very deliberate move on Beethoven’s part to start in this very personal and tender manner, with the piano alone. Overall, especially in the first movement, the Fourth can be characterized as lighter than either the Fifth or the Third. And then of course the second movement is a striking creation, with that very distinctive dialogue between the piano and the orchestra.”

Some scholars, the pianist points out, see that movement as a musical representation of the Orpheus myth, with the Thracian musician-hero venturing into the underworld to rescue his doomed wife Eurydice. “It’s a compelling reading,” he allows. “But taken as just an abstract work of music that second movement remains wonderfully evocative and compelling, while the last movement is one of Beethoven’s most delightful creations.”

The notes on the page, then, are enough—when delivered with the kind of care and attention that this young virtuoso has at his command.

Notes by Alex Varty

Nicolas Ellis, conductor

Nicolas Ellis, conductor Jaeden Izik-Dzurko, piano

Jaeden Izik-Dzurko, piano