AUGUST 8, 2023

BACH, RAMEAU, RESPIGHI

Associate Conductor Giuseppe Pietraroia kicks off VS @Denford Hall—a new series at Glenlyon Norfolk School—with a selection of Baroque and Baroque-inspired favourites. Join the Victoria Symphony for a unique and intimate exploration, and enjoy some post concert refreshment with members of the orchestra.

Ottorino Respighi (1879–1936) is perhaps best known for his set of three colourful orchestral tone poems: Fountains of Rome, Pines of Rome and Roman Festivals. For concertgoers, classical radio programmers and record collectors, the scores have been treasured favourites. The same can be said for another trilogy that Respighi created: his Antiche danze ed arie per liuto (‘Ancient Airs and Dances for Lute’). Together they represent two sides of Respighi’s career, as a leading contributor to the rebirth of symphonic in his native Italy, and as a musicologist with a passion for earlier musical traditions. He brought music of the Renaissance and Baroque to a contemporary audience.

For some, this was a case of putting “old wine in new bottles.” Indeed, there are two sides to how Respighi’s music was received. For much of the 20th century, musical highbrows regarded him as a dabbler or dilettante, in much the same way that Hollywood film composers were once viewed. The French musicologist Henry Prunières—a longtime NY Times correspondent—described Respighi as “an able compromise between the counterpoint of Strauss, the harmony of Debussy, the orchestration of Rimsky-Korsakov – the whole tinted with a little Italian melody.” Perhaps there is a kernel of truth in that comment, since Respighi studied with Rimsky Korsakov while he played viola for a short time in the Russian Imperial Theatre Orchestra in St. Petersburg. Yet conductors such as Toscanini embraced his works, and they became immensely popular through countless radio broadcasts and recordings. Respighi’s catalogue comprises some 200 works, including operas, ballets, orchestral and chamber pieces, as well as vocal and choral scores.

Respighi assembled three suites, (in 1917, 1923, and 1931), based on lute music of the Italian Renaissance period that had been collected by Oscar Chilesotti, a fellow musicologist and early music performer. In contrast to the formal title (‘Ancient Airs and Dances for Lute’), the suites are, in fact, free transcriptions that were adapted to be played by a small orchestra. Each movement in the Suite No. 1 is orchestrated for a slightly different ensemble, drawing on two flutes, two oboes, English horn, two bassoons, two horns, trumpet, harp, harpsichord and strings. There is a regal opening for The Count Orlando, an athletic Gagliarda, a slow and poignant Villanella, and a bright Passo mezzo e mascherada in which the trumpet makes its only appearance. If you wish to explore the other Ancient Airs and Dances, there is a much-loved 1959 recording by Antal Dorati and Philharmonia Hungarica on the Mercury Living Presence label.

In the 1920s, Italian scholars were only just rediscovering Italian baroque music by Vivaldi, including the ubiquitous Four Seasons. In France, there was growing interest in the French baroque, most especially the music of Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683—1784), a close contemporary of Bach, Handel and Telemann. That fascination has continued over the last hundred years, with the growth of historically informed performance practices. Rameau’s epic five-act “tragédie en musique” Dardanus is the source of the excerpts featured in this performance. They were assembled by harpsichordist Charlotte Nediger, who prepared a more fulsome suite of 16 movements from Dardanus for a recording with her colleagues in the Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra. The album won a JUNO award in 2005 (as Classical Album of the Year: Large Ensemble) and also received a Grammy nomination that same year. The recording (which also includes Rameau’s less familiar “opéra-ballet” Le Temple de la Gloire) has since been re-released on the Tafelmusik Media label (tafelmusik.org).

Rameau’s career is curious in that he was 50 years old before he found widespread fame as a composer of serious operas. Prior to that he was a slightly obscure organist and church musician, with a gift for teaching musical theory and harmony. His widely-read treatises brought him to Paris, where his operatic innovations soon created a divide between audiences. Some audience members continued to worship the traditions of Lully—who had by this time been dead for nearly fifty years—while others, including Louis XV, the King of France, embraced Rameau’s elaborate and extravagant entertainments. Dardanus was Rameau’s fifth major production, one of thirty that he produced in his late-blooming career as a composer of staged works over an extraordinarily long life.

So, who is Dardanus, you ask? In Greek mythology he was the son of Zeus and Elektra, and an ancestor of the Trojans. His name lives on in the Dardanelles, the narrow waterway that leads from the Aegean Sea through Turkey towards the Black Sea. Rameau revised and remounted the drama three times, adding more music to each production. Indeed, Dardanus was said to be ‘so laden with music that for three whole hours the orchestral players do not even have time to sneeze’. The present condensation is closer to 15 minutes in duration and features the Ouverture, followed by two Tambourins, an Air Vif, a pair of Menuets and, to close, a Chaconne.

As mentioned, the first half of Rameau’s career was spent as an organist in provincial France. His contemporary, Johann Sebastian Bach (1685—1750) served principally as a church musician throughout his life. He never created an opera himself, but he certainly produced great musical drama in works such as the Christmas Oratorio and St. Matthew Passion. He also fulfilled commissions for both secular and royal audiences, and his monumental output is rich with dance forms of every description.

Bach’s Orchestral Suites were likely composed during his years in Leipzig, where he was Cantor at the St. Thomas Church and its associated music school. He was also the director of the Collegium Musicum, a performance society comprised of some professional musicians alongside students from the University of Leipzig. On a typical Friday night between 1729 and 1741, they would hold a “meeting” at Zimmerman’s coffee house and give a performance that was free to the public. Audiences might have enjoyed works for small ensembles, choral and vocal pieces (including the “Coffee” Canata, of course) and the occasional piece for chamber orchestra.

The Orchestral Suite No. 4 as we know it was adapted from previously existing material. In this work, a series of shorter, courtly dances are preceded by more grandly-scaled French overture, with a characteristic slow, dotted rhythm. Alongside strings and continuo, the musical punctuation of the oboes, trumpets and timpani evoke images of a regal procession in the opening movement. In fact, Bach himself referred to the suites as “Ouvertures,” following the example of French composers such as Lully and Rameau. When they compiled individual movements from ballets or operas (such as Dardanus) for a concert performance, the overture to the complete work was included as the suite’s first movement. Bach follows his Ouverture with two Bourées, a Gavotte, a pair of Menuets and a jubilant Réjouissance as a finale.

Notes: Matthew Baird

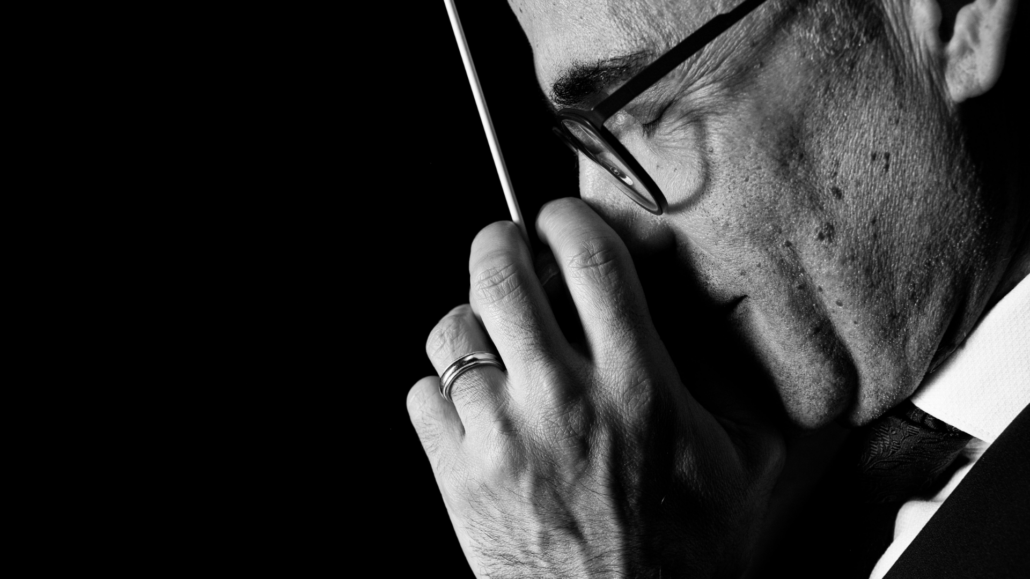

Giuseppe Pietraroia, conductor

Giuseppe Pietraroia, conductor