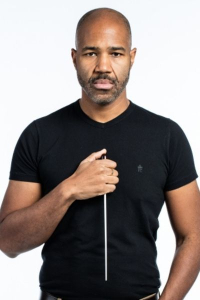

Daniel Bartholomew-Poyser is often billed as a classical-music “disruptor”, and for good reason. Over the course of this young century, and in a variety of roles—CBC radio host, music educator, conductor—he has worked to introduce new audiences to our art form while undercutting any lingering vestiges of its former stuffiness. Whether curating “relaxed concerts” aimed at accommodating autistic children and others with special needs or hosting uproarious romps with violinist and drag queen Thorgy Thor, the Calgary, Alberta native brings an infectious energy to the stage, coupled to impeccable taste.

But there’s little disruption to be found in the program Bartholomew-Poyser is bringing to the Victoria Symphony, beyond the apparent oddity of performing Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring in bleakest November. Instead, we find him in the role of healer or perhaps even shaman, offering a selection of works that will take us on a voyage—sometimes a literal voyage, as in Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington’s paean to the mighty Mississippi, The River—from darkness through beauty to a place of quiet yet radiant hope.

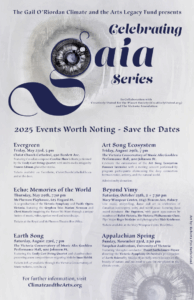

It’s also a concert bill that’s perfectly tailored to one of its sponsors, the Gail O’Riordan Climate and the Arts Legacy Fund, which funds a variety of artistic responses to anthropogenic climate change.

Granted, the concert-opener, Johannes Brahms’ Tragic Overture, has next to no carbon footprint, at least in terms of any overt connection to the natural world. “It is one of my favourite pieces, and I love it and adore it, because it’s terrible in the old sense of the word, where you’re terror-full,” Bartholomew-Poyser explains. “In the middle of the piece he gives us some respite, some calm and some solace, but it’s kind of like when you’re really going through something and it’s just coming at you and for a moment, before the waves hit, you see the sunlight. And then, boom, you’re right back in it again, all the way to th e end.

“The way that Brahms involes terror and tragedy is just like a moving darkness,” he adds. “I wanted something that would contrast very, very strongly with Appalachian Spring. If the Brahms is the darkest flourless chocolate cake, then Appalachian Spring is just a cool drink of water on a hot day. So that’s the journey that we’re taking the audience on. It’s going to be pretty wild.”

Following a classic European confection with an epic American journey is a bold move, and perhaps Batholomew-Poyser wants to connect the waves of terror in the Brahms with the untamed currents in Duke Ellington’s ballet suite. Certainly the score struck fear into some of the members of the ducal orchestra; legend has it that when Ellington’s in-house trombone soloist saw the chart for its sixth movement, “Falls”, he begged to sit that one out.

If you’ve ever looked at the trombone part—or, for that matter, read Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn—you’ll know why. There are not just rapids but full-blown cataracts in this music, treacherous eddies, life-threatening snags, and monstrous creatures in the deep. And there have to be if the piece is to work, but overall it is a passage through beauty. Ellington, no less than Copland, loved the American landscape and was fully equipped as a composer to do it justice.

His methodology was somewhat different, however.

“There’s more than one way to compose,” Bartholomew-Poyser notes. “For example, Beethoven had notebooks that he could write his melodies in, and he’d go over them and over them and over them. And then with Mozart, they arrived finished; he wrote the final copy. Duke Ellington would go into the studio and play 15 bars [of piano], and then his band would rewrite it. And they’d play another 15 bars and send that off to the arranger and he’d write it down, and the next thing they’d do would change it again. It could be extremely frustrating, but that was their process. It was kind of a collaborative process, and Ellington led them through that.

“It allowed him to workshop things in real time,” the conductor adds. In the case of The River, too, he had the able assistance of the Canadian trombonist and composer Ron Collier—like Bartholomew-Poyser, an Alberta native—who is responsible for at least some of the Third Stream touches in the score. But who knows? Ellington knew his way around Maurice Ravel and Claude Debussy, too, and this was a true collaboration.

Nicholas Ryan Kelly’s Earth Beloved is a chance to step outside of the music’s turbulent flow and bask in an almost spiritual radiance.As Bartholomew-Poyser points out, “It’s just incredibly beautiful.

“It’s a fairly new piece—and I remember the first time listening to it, thinking ‘Oh wow, audiences are going to love this piece,’” he continues. “That was my first thought. So, really, it’s about ‘What do you pair that piece with?’ This is a concert that’s about the land. It’s about water. It’s about our earth, in a sense: ‘the earth beloved’. So that is the theme of the concert: the beauty of this planet, and what this planet gives us.”

Ending with Appalachian Spring, despite the calendar, is a natural move. It’s about two people going off to farm the land with faith that the earth will sustain them, and it ends with a prayer-like chorale that will send us out into the rain and the chill with warm hopes.

“This concert has tons of variety,” Bartholomew-Poyser concludes. “For those who love the big, Romantic sound, they get the Brahms. Those who love popular music, who love jazz, they have The River. If you love choral music, if you love a new sound and a fresh, inviting sound… Well, anybody can listen to Earth Beloved and love it. And then the Copland, it’s a classic for a reason. Anybody can come to this concert and enjoy it, whether they’re a serious music lover or hearing stuff for the first time.”

In other words, this program is more delicious than disruptive, and perhaps that’s what we need in these unsettled times.

Notes by Alex Varty

Daniel Bartholomew-Poyser, conductor

Daniel Bartholomew-Poyser, conductor